Disclaimer: The following Timeline contains allegations made in Larson v. Pine County, Case No. 25-cv-2753-NEB/LIB. Claims are supported by exhibits but not yet adjudicated.

Full Timeline: Larson v. Pine County

On a cold January afternoon, I stood outside the Pine County Sheriff’s Office in Hinckley, Minnesota. My purpose was simple: to film publicly visible government property — squad cars, parking lots, the outside of public buildings. Filming from a place the public can lawfully stand is a constitutionally protected activity under the First Amendment.

Deputy Carl Hawkinson approached me. I told him I did not need assistance. Instead of walking away, he became hostile. He lunged toward my recording device, attempting to put his hands on me, and ordered me to identify myself. When I asked if I was being detained, he told me I was not free to go. This is the textbook definition of a seizure under the Fourth Amendment.

Hawkinson’s justification? That I had allegedly violated “data privacy laws” by filming his open laptop screen inside the squad car. But Minnesota law is clear: under Minn. Stat. § 13.05, subd. 5, the duty to protect not-public government data falls on the government, not private citizens. If sensitive information was visible from a public vantage point, that was Hawkinson’s failure, not mine.

January 14, 2022 — The UNLAWFUL Detention

THE ORIGINAL

INCIDENT

Fourth Amendment: Detaining someone without reasonable suspicion or probable cause is unconstitutional.

First Amendment: Retaliating against filming public officials is a violation of free press and free speech.

Minn. Stat. § 609.43 (Official Misconduct): He knowingly acted outside lawful authority.

Minn. Stat. § 609.255 (False Imprisonment): By telling me I was not free to go without cause, he unlawfully restrained my liberty.

Minn. Stat. § 609.224 (Assault – Fear of Harm): His sudden physical lunge created genuine fear of bodily harm.

18 U.S.C. § 242: Deprivation of rights under color of law, a federal crime when willful.

WHY IT WAS

ILLEGAL

After my unlawful detention on January 14, I did what every citizen is told to do: I filed a grievance. I believed that if the Sheriff and County Attorney reviewed the facts, they would see Deputy Hawkinson’s misconduct and take action. I sent complaints to Sheriff Jeff Nelson and County Administrator David Minke, laying out exactly what had happened.

Instead of accountability, I was met with silence from the Sheriff and Administrator. Then, on January 24, 2022, I received a letter from County Attorney Reese Frederickson. The letter was not a good-faith response to my allegations — it was a warning.

Frederickson dismissed my claims as “baseless” and told me that if I continued to press the issue, I could be criminally charged under Minn. Stat. § 609.505 for “false reporting a peace officer crime.” He also suggested I could face defamation lawsuits for speaking publicly about what had happened.

This was not the language of a prosecutor pursuing justice. This was the language of intimidation. The top law enforcement officer in Pine County was using his badge and letterhead to scare me into silence — to make me believe that holding officials accountable could cost me my freedom and my livelihood.

The message was clear: stop speaking out, or we will come after you!

January 20–24, 2022 — A Complaint Met With Threats

COMPLAINT GIVEN TO

PINE COUNTY SHERIFF

JEFF NELSON

COMPLAINT EMAILED TO

PINE COUNTY ADMINISTRATOR

DAVID J. MINKE

click to read the initial complaint

THE RESPONSE RECIEVED BY

PINE COUNTY ATTORNEY

REESE FREDERICKSON

First Amendment Retaliation: Threatening criminal charges and lawsuits in direct response to protected speech and petitioning activity is retaliation that chills constitutional rights.

Minn. Stat. § 609.27 (Coercion): Using threats of prosecution to force someone to stop exercising lawful rights — like filing complaints or publishing videos — is unlawful coercion.

Minn. Stat. § 609.43 (Official Misconduct): By issuing a formal letter on County Attorney letterhead that relied on a knowingly false legal justification (claiming I violated Chapter 13 by filming), Frederickson acted beyond lawful authority and unlawfully injured my rights.

Minn. Stat. § 609.43(4) (False Reports by Officials): An official who creates an “official report” that is false in any material respect commits misconduct. Frederickson’s letter falsely claimed I had violated data-practices law, despite Chapter 13 placing the duty to protect not-public data on the government, not the public.

Minn. Stat. § 609.50 (Obstruction of Legal Process): Using false law to shield Hawkinson’s misconduct and intimidate me from pursuing complaints obstructed the legal process.

18 U.S.C. § 242: Willfully misrepresenting statutes to justify unlawful detention and intimidate a citizen can qualify as deprivation of rights under color of law — a federal crime.

WHY IT WAS

ILLEGAL

When the threats didn’t work, Pine County escalated. On February 22, 2022, Hawkinson filed a Harassment Restraining Order (HRO) against me. By early March, County Attorney Reese Frederickson confirmed he would personally represent Hawkinson in that civil matter — despite having just used his official office weeks earlier to dismiss my complaint against Hawkinson as ‘baseless.’ This dual role was a blatant conflict of interest and a misuse of prosecutorial authority.

This petition was not built on threats I made, or acts of violence, or any true danger. It was built on my speech. Hawkinson cited my YouTube livestreams where I exposed misconduct, my picketing campaign in Hinckley, and the sign I carried that read boldly: “FACE OF TYRANNY.” He even tried to use my lawful protests in front of government buildings as evidence of “harassment.”

Hawkinson submitted third-party YouTube comments in his sworn petition as if they reflected my harassment of him — which is the stated purpose of the HRO petition form. Because the petition is signed under penalty of perjury, he attested to their accuracy and truthfulness despite knowing they were not mine. As a trained law enforcement officer familiar with legal forms, this was not a mistake; it was a willful misrepresentation.

This wasn’t about safety. This was about power. The County Attorney and a deputy were now shoulder-to-shoulder, weaponizing the court system to silence one citizen for embarrassing them. They weren’t defending law and order; they were defending their reputations.

The order sought to ban me from courthouses, the Sheriff’s Office, and other public spaces — the very places where I had a right to petition, to protest, and to hold officials accountable. It was an attempt to make my lawful dissent illegal. It was the clearest signal yet: Pine County would rather twist the courts than face the truth.

February 22, 2022 — A Retaliatory Restraining Order

click the image and read the petition.

See the “evidence of harassment”

alleged against the respondent for your self.

THE ILLEGAL

PETITION/ORDER FOR HARRASSMENT RESTRAINING ORDER

First Amendment Retaliation: Using a restraining order to silence protest signs, livestreams, and public criticism is retaliation against constitutionally protected speech and petitioning activity.

Viewpoint Discrimination: The petition targeted me not for threats or violence, but because my message called officials the “FACE OF TYRANNY.” Government may not punish or restrict speech based on viewpoint.

Minn. Stat. § 609.505 (False Reporting): Hawkinson knowingly attributed third-party YouTube comments to me in a sworn court filing. That is a false report intended to trigger legal action.

Minn. Stat. § 609.48 (Perjury): Making false material statements under oath — such as misrepresenting others’ words as mine — constitutes perjury.

Minn. Stat. § 609.43 (Official Misconduct): Frederickson misused his prosecutorial office to act as counsel in a deputy’s personal civil matter, acting beyond lawful authority to oppress protected speech.

42 U.S.C. § 1983: Misusing state court process to chill constitutionally protected speech is a deprivation of rights under color of law.

Supreme Court Precedent — Snyder v. Phelps (2011): Even offensive or unsettling protest signs at sensitive events are protected by the First Amendment. My peaceful “FACE OF TYRANNY” picketing outside government buildings was political speech — the highest form of protected expression.

WHY IT WAS

ILLEGAL

March–May 11, 2022 — Wearing Two Hats:

The Prosecutor Becomes the Deputy’s Private Lawyer

After filing the HRO in February, Pine County didn’t just lean on the courts—they merged public power with private interest.

On the docket in 58-CV-22-80, a Certificate of Representation appears: County Attorney Reese Frederickson lists himself as counsel for Deputy Carl Hawkinson in the civil HRO. This wasn’t a criminal case brought by the State. This was a personal restraining order—and the top prosecutor in Pine County stepped in as the deputy’s lawyer.

Why is that a big deal? Because just days earlier, this same prosecutor had “cleared” Hawkinson in response to my complaint, telling me in writing that I was “baseless” and even insinuating I’d broken the law. Then, instead of staying neutral, he crossed the line: he became the deputy’s private advocate in a case aimed at curbing my speech and protest.

The fallout was immediate. The court granted an ex parte order that restricted my access to government buildings while the case was pending—a prior restraint that came down before I ever had a chance to be heard. From there, the process turned into a grind: hearings were continued and rescheduled more than once, with date changes funneled through County Attorney Reese Frederickson, who was functioning as Hawkinson’s lawyer rather than a neutral public official. Emails flew; calendars shifted. Every practical decision in the HRO ran through Reese.

Facing mounting delays and an order that hampered my ability to petition and film, I reached out for help. A Minneapolis civil-rights group—Communities United Against Police Brutality (CUAPB)—stepped in, paired me with an attorney, and offered to cover the legal bill so I could push back effectively. With counsel on board, the temperature changed: the other side became open to a negotiated exit.

On May 11, 2022, we reached a settlement. I agreed to limited, expedient terms that would end the HRO quickly, consistent with my lawyer’s advice to stop the bleeding and return to the bigger constitutional fight. The terms included temporary changes to certain videos (such as retitling/removal for a short period) and other narrow conditions designed to close the case. There were no findings against me, no admission of harassment, and the HRO was dismissed.

Even so, the settlement’s narrow restraints slowed my advocacy in the short term and were later waved back at me when I continued seeking accountability—illustrating exactly why prior restraints and speech-linked conditions are so dangerous. Expediency ended the immediate threat; it did not sanitize the misuse of public office that got us there.

“this is called conflict of interest”

“A publicly funded prosecutor represented a deputy in a private civil case aimed at curbing speech—after ‘clearing’ him. Public power, private benefit.”

Above: What the Law Allows (and Doesn’t)

Minnesota Statute § 388.051 spells out the duties of a county attorney. Those duties are strictly public-facing: represent the county in cases where the county is a party, prosecute crimes on behalf of the state, and advise county officers in their official duties. Notice what’s not on that list: there is no authorization for a county attorney to act as personal counsel for a deputy in a private civil matter. The statute’s silence is itself limiting — if the legislature didn’t grant the authority, the county attorney doesn’t have it. Public officers are bound to the duties the law gives them, nothing more.

When Reese Frederickson filed a Certificate of Representation [see below] to appear as Hawkinson’s lawyer in case 58-CV-22-80, he wasn’t doing county work. He was crossing into a deputy’s personal dispute, using the prestige and resources of public office for a private cause of action. By law, that’s outside his lane.

Below: How Conflict-of-Interest Rules Apply (and Were Violated)

The Minnesota Rules of Professional Conduct add another layer: they bar public lawyers from conflicts of interest that compromise their independence.

Rule 1.7 prohibits representation where the lawyer’s responsibilities to another client, or to their own role as a public official, would materially limit their ability to represent a private client.

Rule 1.11(d) specifically restricts current government lawyers from representing private clients in matters where their public role creates leverage or conflicting duties, unless explicit, lawful consent is given.

Reese had just “cleared” Hawkinson in response to my complaint, acting in his public capacity. Then he switched hats and became Hawkinson’s private lawyer in the HRO — the very proceeding connected to my protected speech. That’s a textbook conflict: he was no longer an impartial prosecutor, but an advocate against a citizen he had already threatened in writing. No statutory authority, no ethical clearance, no waiver from the state — just an official using his badge of office to wage a private fight.

This is why the law calls it official misconduct: when a public officer steps outside the duties written in law and uses their position to harm the rights of others, the office itself is misused. Frederickson’s appearance in 58-CV-22-80 wasn’t just a paperwork detail. It was the fusion of public authority with private retaliation.

Here appears Pine County Attorney

Reese Frederickson

on behalf of

Carl Hawkinson

“This document — filed in court — shows Reese Frederickson entering his appearance as private counsel for Deputy Hawkinson. That is something the law simply does not allow.”

County attorneys are limited to public work.

Minnesota law authorizes county attorneys to represent the county, advise county officers, and prosecute crimes—not to act as a deputy’s private counsel in a civil HRO aimed at a critic. Reese’s appearance as Hawkinson’s lawyer exceeded that authority.

Government-lawyer conflict rules.

As a sitting public lawyer, Reese was bound by conflict-of-interest rules (e.g., current-client conflicts and special conflicts for government lawyers). “Clearing” Hawkinson as a prosecutor and then personally representing him in a civil case tied to my speech created a prohibited conflict and leveraged public power for a private advantage.Misuse of public office & resources (official misconduct).

Using public letterhead, authority, and staff time to advance a private civil petition—especially one targeting protected speech—constitutes acting beyond lawful authority and injuring a citizen’s rights.Prior restraint & burdens on petitioning.

The ex parte order restricted access to public buildings and chilled filming/petitioning before a full hearing—an impermissible prior restraint on core First Amendment activity.Retaliatory litigation tactics.

Continuances and maneuvering that keep speech-restrictive orders in place while a prosecutor acts as private counsel amplify the retaliatory effect, supporting liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for actions taken under color of law to chill protected expression.Unconstitutional conditions (settlement).

The government may not condition relief or procedural benefits on surrendering speech rights. Agreeing—on counsel’s advice—to temporary video changes to end a meritless HRO does not retroactively legalize the underlying retaliation or the prosecutor’s role conflict.

WHY IT WAS

ILLEGAL

“On May 11, 2022, after months of continuances and an ex parte order that kept me away from public buildings, the HRO case ended in settlement. By then, I had support from Communities United Against Police Brutality (CUAPB), a Minneapolis-based civil-rights network. CUAPB paired me with an attorney and even offered to cover the bill so I could defend myself on equal footing.

We entered mediation. I remember saying, “It feels like we both lost something.” That was the tone: not vindication, but expedience. I wanted to move forward; they wanted me quiet.

The written terms were narrow:

I agreed to temporarily remove or retitle specific YouTube videos that named Deputy Hawkinson — including videos of my detention and protests.

After a set period, the restrictions expired, and the case would be dismissed.

In return, the HRO was dismissed outright, one year later. There were no findings of harassment, no admission of wrongdoing, and no lasting restrictions.

On paper, it looked like compromise. But in reality, it was a gag order in disguise. Even though the settlement only spoke to videos, the chilling effect reached far beyond. For roughly a year, I felt boxed out of filing new complaints or speaking freely about Hawkinson and Nelson — because any attempt could be twisted as violating “the spirit” of the deal. That hesitation is exactly what the First Amendment is meant to prevent. To be clear, The order did not prevent me from filling formal complaints.

Expediency does not make unconstitutional terms lawful. No agreement can sanitize retaliation, and no settlement can license the government to silence speech.”

May 11, 2022 – 2023 — The Settlement That Silenced Me

Unconstitutional Conditions: Government cannot demand the removal or alteration of videos critical of public officials as the price of dismissing a case. Perry v. Sindermann (1972).

Prior Restraint: Forcing the removal or retitling of political videos is a textbook prior restraint — “the most serious and least tolerable” infringement of free expression.

Chilling Effect Beyond the Page: Even though the written terms targeted videos, their practical effect discouraged me from filing new complaints or criticizing Pine County officials — chilling protected petitioning and speech.

Void as Against Public Policy: Courts cannot enforce agreements that restrict core constitutional rights. Any settlement that conditions relief on silencing protected speech is invalid on its face.

Retaliation by Process: This settlement did not come from neutral bargaining power. It was born of an abusive HRO petition, filed in retaliation for speech, and leveraged into “consent” under duress of government authority.

WHY IT WAS

ILLEGAL

“The year after the settlement was not restful. Instead of closure, I was left with a gnawing doubt that only grew stronger with time. Night after night, I replayed the hearings in my head, revisiting every word, every pause, every compromise. I lost sleep over the constant, nagging sense that I had made the wrong choice. I had avoided the drawn-out fight, yes, but at the cost of my own peace.

I kept circling back to the same thought: I should have fought the HRO instead of settling. That single decision weighed on me more than the hearings themselves. The agreement had muted me for a year, and while it ended the immediate pressure, it also gave the appearance that Pine County’s retaliation had worked.

By mid-2023, the settlement terms had finally expired. The HRO was formally dismissed with prejudice. The gag was gone, the file was closed, and for the first time since January 2022 I was free to step forward without that paper weight around my neck. That moment mattered — it meant that even on their own terms, they had failed.

But instead of feeling relief, I felt restless. I had spent the entire year reading, studying, and trying to piece together what had happened. I came to see how the HRO statute itself carved out protection for constitutionally protected activity, meaning that my protest signs and videos never should have been treated as harassment. I saw more clearly how Reese’s dual role as both prosecutor and personal counsel was a conflict that went beyond bad optics into outright illegality. I saw how the settlement terms, even though I had agreed to them, were fundamentally unenforceable because no government body can contract around the First Amendment.

I didn’t yet have the full picture — the emails and internal documents that would come years later — but I had enough. Enough to know that what was done to me was not just unfair, but unlawful. Enough to know that staying silent was exactly what they had wanted all along.

So this time, I chose to do it differently. No more hallway conversations or passing comments that could be brushed aside and forgotten. I put it in writing. I drafted a formal written complaint to Sheriff Jeff Nelson. In that document, I laid out in detail how the HRO had been misused as a weapon, how County Attorney Reese Frederickson had stepped outside his lawful duties to act as a deputy’s private lawyer, and how my constitutional rights had been trampled at every stage.

It was my way of saying: the silence is over..”

2023 – 2024 — Picking at the Scab, Renewed Complaints

The Sworn

Complaint

“It is my firm belief

that the sole purpose of this HRO was to

suppress my constitutional rights.”

“At the very same time that I filed my written complaint with Sheriff Nelson, I prepared a second document: a detailed letter to the presiding judge.

I believed the judge would be outraged once he saw the full picture of what had been done in his courtroom. In that letter, I explained how the HRO petition twisted peaceful protest into “harassment,” how Pine County’s own prosecutor abandoned his duty to act as Hawkinson’s personal lawyer, and how the settlement had forced unconstitutional conditions onto speech. I laid out the nuance — point by point — in the way that only someone who had lived it could explain.

What I hoped to accomplish was not to re-litigate the case, but to call the court back to its duty. I wanted recognition that the process had been abused, that the courtroom had been turned into a weapon against the very rights it was meant to protect. I asked the judge to look directly at the misuse of procedure and to acknowledge the constitutional violations that had never been corrected.

I thought a judge — above all others — would see the danger in allowing government officials to hijack the legal process to silence a critic. I hoped he would intervene, or at the very least, respond.

Instead, the rest of 2024 was spent waiting. No acknowledgment. No reply. Just silence.”

Letter to Chief Judge

Stoney Hiljus

January 4, 2024 - CIRCLINIG THE WAGONS

“Sheriff Jeff Nelson did respond — at least on paper. On January 4, 2024, I received a letter that, at first glance, looked official, measured, and complete. But when I read it closely, I realized what it truly was: a non-response dressed up as a reply.

Instead of addressing the actual allegations I had sworn under penalty of perjury, Nelson’s letter restated a selective version of events. He repeated his earlier position that Deputy Hawkinson had not broken the law, offering nothing new beyond the same assertions I had already challenged. Critical details from my complaint were omitted entirely. There was no mention of the prosecutor’s dual role, no acknowledgment of the fabricated “harassment” narrative, and no attempt to reconcile how constitutional rights could be treated as criminal conduct.

To the casual eye, the sheriff’s letter might seem like he had “looked into it.” But to anyone familiar with proper investigative practice, it was clear he hadn’t investigated at all — he had summarized, minimized, and then closed the door. What he called “review” amounted to little more than rubber-stamping his own department’s earlier misconduct.

The omissions were telling. By leaving out entire sections of my sworn complaint, Nelson avoided confronting the most damning evidence: that his deputy’s petition was built on knowingly false claims, that the County Attorney had stepped into a role he had no lawful authority to assume, and that the end result was a prior restraint on speech disguised as a civil order. His silence on those points was louder than anything he wrote.

And that was the heart of the problem: Nelson’s “response” was not a true investigation, but an act of institutional protection. It circled the wagons around his deputy, around the prosecutor, and around the County itself. For me, it was confirmation that the chain of command in Pine County was not designed to uncover the truth, but to bury it.”

“The Response That Wasn’t — and the Silence That Spoke Volumes”

Top: Nelson’s polished letter. Bottom: his internal ‘review’ narrative.

Sheriff

Jeff Nelson

Here’s why Sheriff Nelson’s so-called ‘response’ failed the law, failed the public, and failed the Constitution.

Sheriff’s duty under Minnesota law

Minnesota sheriffs are bound by statute to investigate crimes reported to them and to protect the rights of citizens without bias. A sworn complaint alleging perjury, misuse of office, and constitutional violations should have triggered a full and impartial inquiry, or at the very least a referral to an outside agency to avoid conflicts of interest. Simply restating prior conclusions does not meet that duty.Failure to investigate

Nelson’s letter and internal “primary report” did not address the facts laid out in my sworn complaint. Instead, they recycled old conclusions, omitted entire allegations, and ignored the prosecutor’s dual role. This was not an investigation, but a summary dismissal. Under Minn. Stat. § 609.43 (official misconduct), knowingly failing to perform duties in good faith or minimizing criminal allegations to shield colleagues can itself constitute unlawful conduct.Omissions as cover-up

By leaving out the most critical allegations — perjury in the HRO petition, misuse of public office, and retaliation against speech — Nelson avoided the very questions his office was obligated to answer. His silence on those points was not neutral; it operated as protection for his deputy and the county attorney, effectively circling the wagons. Courts have repeatedly held that selective or bad-faith review undermines due process and erodes the rule of law.Reasonable expectation of a citizen

A reasonable person filing a detailed sworn complaint would expect acknowledgement of the specific allegations, an impartial assessment of the evidence, and corrective steps if misconduct was confirmed. At minimum, the complaint should have been referred to an independent investigator or neighboring jurisdiction. What I received instead was a “non-response” that shielded officials from accountability.Retaliation by process

When a sheriff ignores substance and issues a hollow response, the effect is the same as retaliation. By refusing to grapple with my allegations, the county ensured the underlying misconduct was preserved, and the chilling effect of the HRO process remained intact. Federal law (42 U.S.C. § 1983) recognizes such omissions, when done under color of law, as actionable deprivations of rights.

WHY IT WAS

ILLEGAL

"Sheriff Nelson’s letter had been a response that wasn’t. Judge Hiljus’s refusal to answer at all was the silence that spoke volumes. By the close of 2024, every door I had tried to open was either shut or led back into the same circle of protection. The wagons had been drawn tight. And yet, silence has a way of leaving traces. If the officials of Pine County and the court would not speak, then I would have to find those answers in the records they left behind. That is what April 2025 delivered."

In 2022, when Hawkinson filed his HRO petition, he pointed the judge to IR:22000150 — the Pine County incident report. That told me a narrative report existed, but the petition didn’t show it. I had to FOIA it to see the actual words. That first version landed in my NABL News inbox, and I saved it. On paper, it looked like what it was: an unresolved account of my unlawful detention. It didn’t clear me. It didn’t damn me. It left the door wide open for Reese and Hawkinson to spin their narrative.

Fast forward to April 2025. I re-requested the same report. This time, Pine County handed me something different. The “official” 2025 copy now claimed Hawkinson knew by the end of the detention that no crime had occurred. That line hadn’t existed before. And here’s the kicker: by 2025 they were willing to admit it on paper — but they hadn’t admitted it when it counted, when a judge was deciding whether to brand me a harasser. That’s not a mistake. That’s manipulation.

I didn’t just trust my gut. I dug up my old 2022 email, pulled the attachment, and ran the two versions side by side. AI confirmed the edits in a fraction of a second. The metadata confirmed the rest: the file had been altered after the HRO was filed. The judge never saw the line that cleared me. The County kept that back, weaponized silence, and let me walk into court branded as unstable — all while sitting on proof I was telling the truth.

That is hiding exculpatory evidence. Exculpatory means evidence that proves innocence. They had proof I hadn’t committed a crime. They had proof my complaints weren’t false. And instead of putting that before the court, they buried it. Why? To shield a deputy. To shield a county. To silence me. That is not incompetence — that is calculated obstruction.

And the motive? Reese’s own words. On March 4, 2022, he emailed Kanabec County asking for “any incident reports or dispatch/call logs” where I had complained about law enforcement or Pine County deputies. Not crimes. Not threats. My complaints. That’s what he was hunting. That’s why they bent the record. They weren’t investigating wrongdoing. They were investigating me.

Their edits admit what they concealed: I hadn’t committed a crime, and my accusations were never false. They knew it the whole time. And they buried it. That is the proof. That is the pattern. And that is why April 2025 detonated the whole case. For the first time, I didn’t just have suspicion. I had their own words, their own edits, and their own metadata. I had motive, method, and concealment in black and white. And with that, the next step became unavoidable. May would be about turning paper into pressure.

April 2025 — Records, Metadata, and Motive

The Original

Report

click the images to view the entire reports

The Modified

Report

AI GENERATED

ANALSYS

OF MODIFIED REPORTS

Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963): The Supreme Court made it clear: the State cannot suppress evidence favorable to the accused. By presenting the 2022 version to the judge while sitting on the exculpatory 2025 language, Pine County committed a textbook Brady violation. They denied me due process by hiding the very line that cleared me.

Minn. Stat. § 13.03 — Data Practices Act: This statute guarantees access to government records as they exist. Providing an altered version in place of the original is not access; it is deception. Minnesota law does not allow counties to rewrite history.

Minn. Stat. § 609.43 — Official Misconduct: When a County Attorney and deputies conspire to falsify or conceal reports to shield themselves and their colleagues, they cross the line from public duty to personal protection. That is criminal misconduct under Minnesota law.

42 U.S.C. § 1983 — Civil Rights Act: The First Amendment protects the right to petition the government. Retaliating against those petitions by altering records, suppressing exculpatory evidence, and using the false version to obtain a harassment order is a deprivation of constitutional rights under color of law.

18 U.S.C. § 1519 — Federal Obstruction of Justice: This federal statute punishes those who knowingly alter, conceal, or falsify records with the intent to obstruct an investigation or proceeding. Pine County altered the report after judicial reliance, concealed the edit trail in metadata, and substituted the amended version as the “official” record. That is obstruction, plain and simple.

WHY IT WAS

ILLEGAL

"On April 23, 2025, I stopped knocking on Pine County’s door and took my fight to every oversight body with authority to act. I didn’t do it piecemeal — I did it as a coordinated strike. Every complaint was drafted with exhibits, citations, and statutory authority so that no official could pretend I hadn’t done my homework.

I filed with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Only the DOJ has criminal authority under 18 U.S.C. § 242 to prosecute officials who willfully deprive a citizen of rights under color of law. That statute exists for moments exactly like mine: when local prosecutors, sheriffs, and judges are compromised by the same misconduct. My filing spelled it out — the unlawful detention, the retaliation through a Harassment Restraining Order, the refusal to investigate, the suppression of exculpatory evidence. This wasn’t one deputy’s mistake. It was an entire county government acting in concert against protected speech.

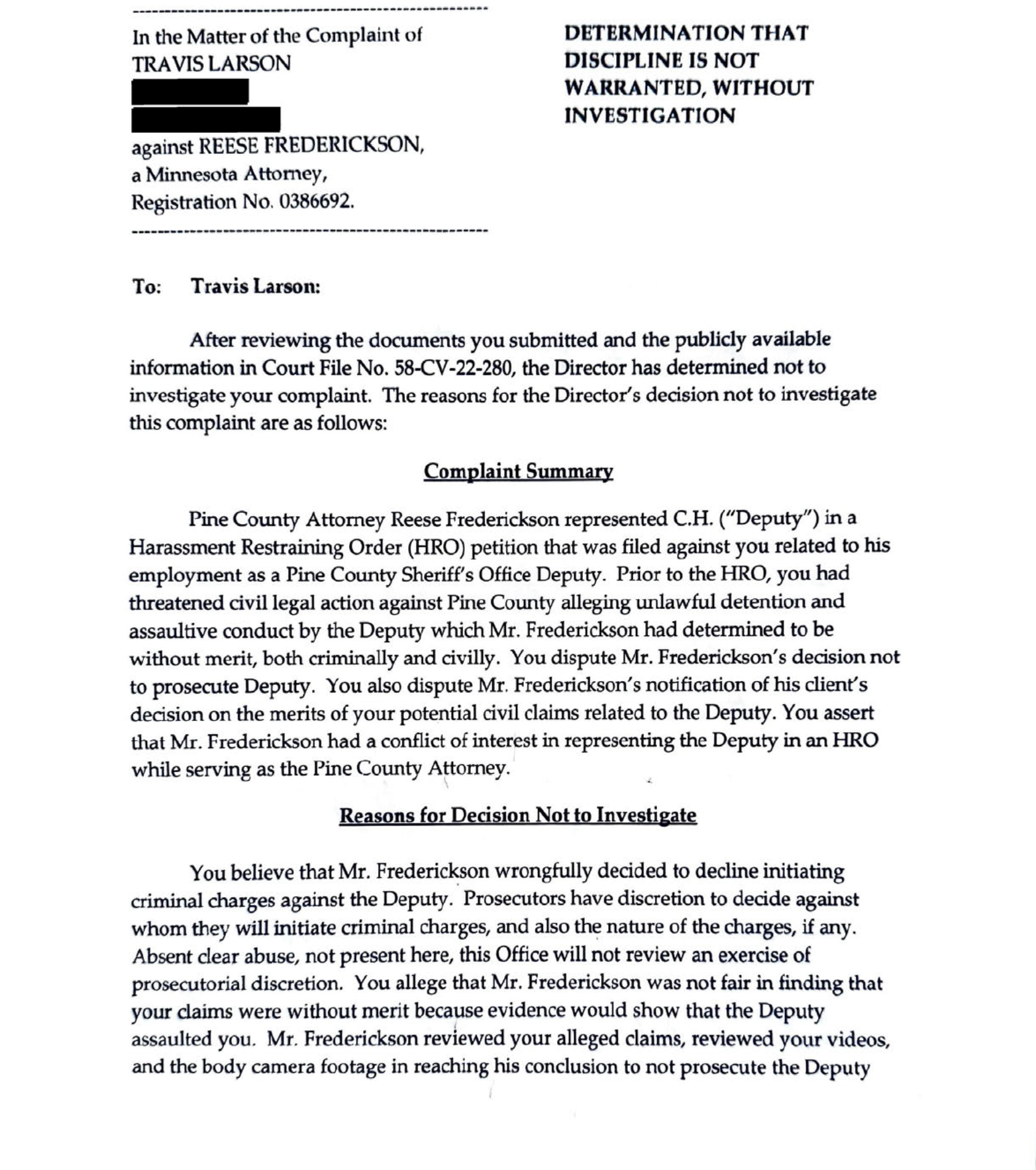

I submitted an ethics complaint to the Minnesota Office of Lawyers Professional Responsibility (OLPR) against Pine County Attorney Reese Frederickson. I didn’t rely on rhetoric — I cited Minn. R. Prof. Conduct 1.7 and 1.11, which forbid conflicts of interest for government lawyers. I attached Frederickson’s January 24, 2022 denial letter, where he threatened me with prosecution for “false reporting.” I paired it with the Certificate of Representation he filed in the HRO, proving he personally represented Deputy Hawkinson in a civil case — a role Minnesota Statute § 388.051 does not authorize. A county attorney may represent the state or the county, not moonlight as a deputy’s private lawyer to silence a critic. That wasn’t gray area — it was black letter law.

I filed complaints with the Minnesota Board of Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST Board) against both Deputy Hawkinson and Sheriff Nelson. POST is the licensing authority for every officer in the state, charged with enforcing standards under Minn. R. 6700.1600. Those standards prohibit unlawful conduct, failure to perform duties, and conduct that undermines public trust. Hawkinson’s January 14, 2022 detention checked every box: he restrained me without legal basis, grabbed for my phone, and then retaliated through the courts. Nelson’s misconduct was just as clear. He received a verbal complaint and a written grievance, then ignored them both. For two years, he had the evidence in his hands — including Hawkinson’s own report — and chose not to act. POST wasn’t just another option; it was the statutory backstop when sheriffs refuse accountability.

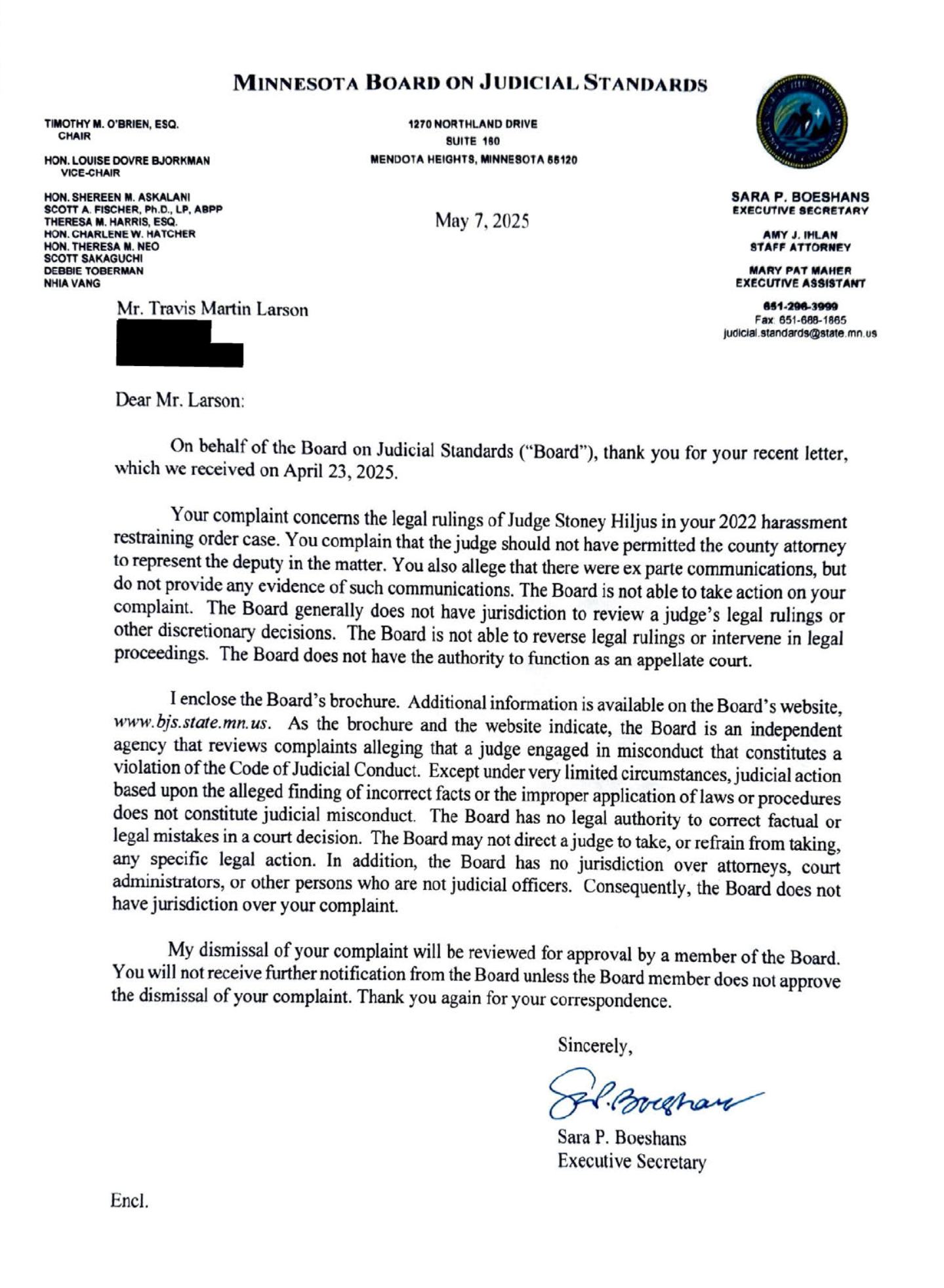

Finally, I wrote to the Minnesota Board on Judicial Standards. My complaint wasn’t about whether a ruling was right or wrong — it was about judicial ethics. I laid out how Judge Stoney Hiljus allowed Frederickson to serve as both prosecutor and personal counsel in the same matter, a dual role that violated the very canons of judicial conduct designed to protect impartiality. The Minnesota Code of Judicial Conduct, Canons 1 and 2, require judges to avoid impropriety and preserve confidence in the courts. By letting Frederickson stand shoulder-to-shoulder with his deputy, Hiljus presided over a conflict that undermined both. My complaint asked the Board to do its one job: enforce the ethical boundaries that keep courts from becoming tools of retaliation.

This wasn’t one grievance. It was five— each backed by law, evidence, and clear misconduct. On April 23, I gave every watchdog the chance to prove they could still bark."

April–June 2025 — Oversight Complaints & Responses

United States

Department of Justice

Complaint

The Complaints

Office of Lawyer

Professional Responsibility

Complaint

Against Attorney Frederickson

Minnesota Board on

Judicial Standards

Complaint

Against Judge Hiljus

Complaint

Against Deputy Hawkinson

Peace Officer Standards and Training

Complaint

Against Sheriff Nelson

The Responses

"After April 23, 2025, I waited. I had done what every citizen is told to do when local officials cross the line — I went to the oversight bodies. DOJ, OLPR, POST, and MBJS each had my complaints in their hands, each backed by statutes, exhibits, and sworn facts. I expected resistance, but I also expected at least one of them to acknowledge the obvious: that Pine County’s officials had stepped outside the law. These were the watchdogs, the agencies sworn to guard the guardians. By May and June, their answers arrived. What came back wasn’t vindication for Pine County. It was avoidance, phrased four different ways."

"The DOJ logged my civil rights complaint under 18 U.S.C. § 242 on April 23, 2025 — Record No. 601096-MQJ. Two months later, their answer arrived. A form letter. It said they focus on ‘patterns of abuse’ and ‘systemic issues,’ not ‘individual problems.’

But my filing wasn’t one incident. It documented an entire county acting in concert: a deputy who unlawfully detained me, a sheriff who refused to investigate, and a prosecutor who weaponized a retaliatory HRO. That is the definition of a pattern. The statute doesn’t require multiple victims — it criminalizes any willful deprivation of rights under color of law. One intentional violation is enough.

The DOJ never said Hawkinson’s detention was lawful. They never said Nelson’s refusal to act was justified. They never defended Reese’s dual role. They simply stepped back. By framing a coordinated retaliation as an ‘individual issue,’ the only federal agency empowered to enforce § 242 left Pine County’s misconduct untouched. That silence wasn’t clearance — it was abdication."

The United States Department of Justice

"OLPR dismissed my April 23, 2025 ethics complaint against County Attorney Reese Frederickson. They didn’t deny the facts: that Frederickson cleared Hawkinson as prosecutor, then appeared in court as his lawyer in a retaliatory HRO. Instead, their letter invoked ‘prosecutorial discretion’ and treated it as if Reese were representing a county employee in an official capacity.

That reasoning collapses under the statute. Minn. Stat. § 609.748 is clear: a Harassment Restraining Order may only be petitioned by an individual. Hawkinson wasn’t standing in court as “the Pine County Sheriff’s Office.” He was standing there as Carl Hawkinson, a private petitioner, suing a citizen critic. That means Reese wasn’t representing the county. He was moonlighting as his deputy’s personal lawyer.

The rules on conflicts of interest — Minn. R. Prof. Conduct 1.7 and 1.11 — forbid a government lawyer from switching sides like that. OLPR didn’t declare Reese’s conduct lawful. They just refused to apply the rules, calling it discretion. Discretion governs charging decisions. It does not authorize a county attorney to drag a citizen into court on behalf of his own deputy."

The Minnesota Office of Lawyer Professional Responsibility

"The Judicial Standards Board answered my April 23, 2025 complaint on May 7. Their letter was short: they said they could not review ‘judicial rulings.’ That was the entire response. But my complaint was not about a ruling. It was about ethics.

I told them Judge Stoney Hiljus allowed County Attorney Reese Frederickson to stand in two roles at once: as Pine County’s prosecutor and as Deputy Hawkinson’s personal lawyer in a retaliatory HRO. That is not a ‘judicial ruling.’ It is a failure of oversight. The Minnesota Code of Judicial Conduct, Canons 1 and 2, require judges to avoid impropriety and maintain public confidence in the courts. By letting Reese cross that line, Hiljus presided over a conflict that undermined both.

The Board did not say Hiljus acted properly. They did not justify the dual role. They simply avoided it. By stamping it a ‘ruling,’ they washed their hands of judicial ethics. That is not enforcement. That is evasion."

The Minnesota Board on Judicial Standards

"The POST Board was supposed to be the backstop — the licensing authority that enforces professional standards when sheriffs and deputies cross the line. On April 23, 2025, I filed two complaints: one against Deputy Carl Hawkinson for unlawfully detaining me, grabbing at my phone, and then retaliating through a Harassment Restraining Order; and one against Sheriff Jeff Nelson for ignoring my verbal and written complaints for more than two years.

On June 12, their answer came back stamped ‘Confidential.’ Inside, the letter claimed my complaints were outside their jurisdiction. They listed a narrow menu of situations they act on: felony convictions, fraudulent licensing, failure to meet minimum qualifications, or violation of professional standards. Then they pointed to the very rule that applies — Minn. R. 6700.1600. That rule explicitly forbids officers from violating laws, neglecting their duties, or acting in ways that undermine public trust. Hawkinson and Nelson did all three.

By pretending jurisdiction only exists after a felony conviction, POST stripped its own standards of meaning. The statute that governs them, Minn. Stat. § 626.8432, doesn’t limit their authority that way. It empowers POST to enforce standards against officers who violate them — full stop.

The POST Board didn’t clear Hawkinson or Nelson. They didn’t dispute the detention happened or that Nelson refused to investigate. They just chose not to apply their own rules. And by stamping the letter ‘Confidential,’ they signaled what this really was: an accountability board burying misconduct out of public sight."

The Minnesota Peace Officer Standards and Training

"Every response shared the same DNA: silence dressed up as procedure. Not one agency said my rights were intact. Not one justified Hawkinson’s detention, Nelson’s refusal to investigate, or Frederickson’s dual role. They just recited reasons to look away. That wall of refusal became my turning point. If the watchdogs wouldn’t bite, I would drag Pine County into court myself. First with criminal complaints, then with civil ones — because the record I had built wasn’t going to die in a drawer."

June -July 2025 - The Criminal and Civil Complaints

“I didn’t just file another grievance, I filed criminal complaints. Not rants, not YouTube videos — sworn charging documents built on statute, evidence, and probable cause. Every line was anchored in law: Minn. Stat. § 609.43 (Official Misconduct), § 609.255 (False Imprisonment), § 609.505 (False Reporting), § 609.498 (Retaliation), and § 609.175 (Conspiracy). I even pulled the federal hammer — 18 U.S.C. § 242 — deprivation of rights under color of law. These weren’t essays; they were indictments.

One for Deputy Carl Hawkinson: the deputy who lunged, detained, and then doubled down with a false HRO. One for Sheriff Jeff Nelson: the sheriff who circled the wagons, signed off on altered reports, and looked the other way. One for County Attorney Reese Frederickson: the prosecutor who threatened me in writing, then turned around and became Hawkinson’s personal lawyer. I DEMAND arrest warrants. I demanded accountability.

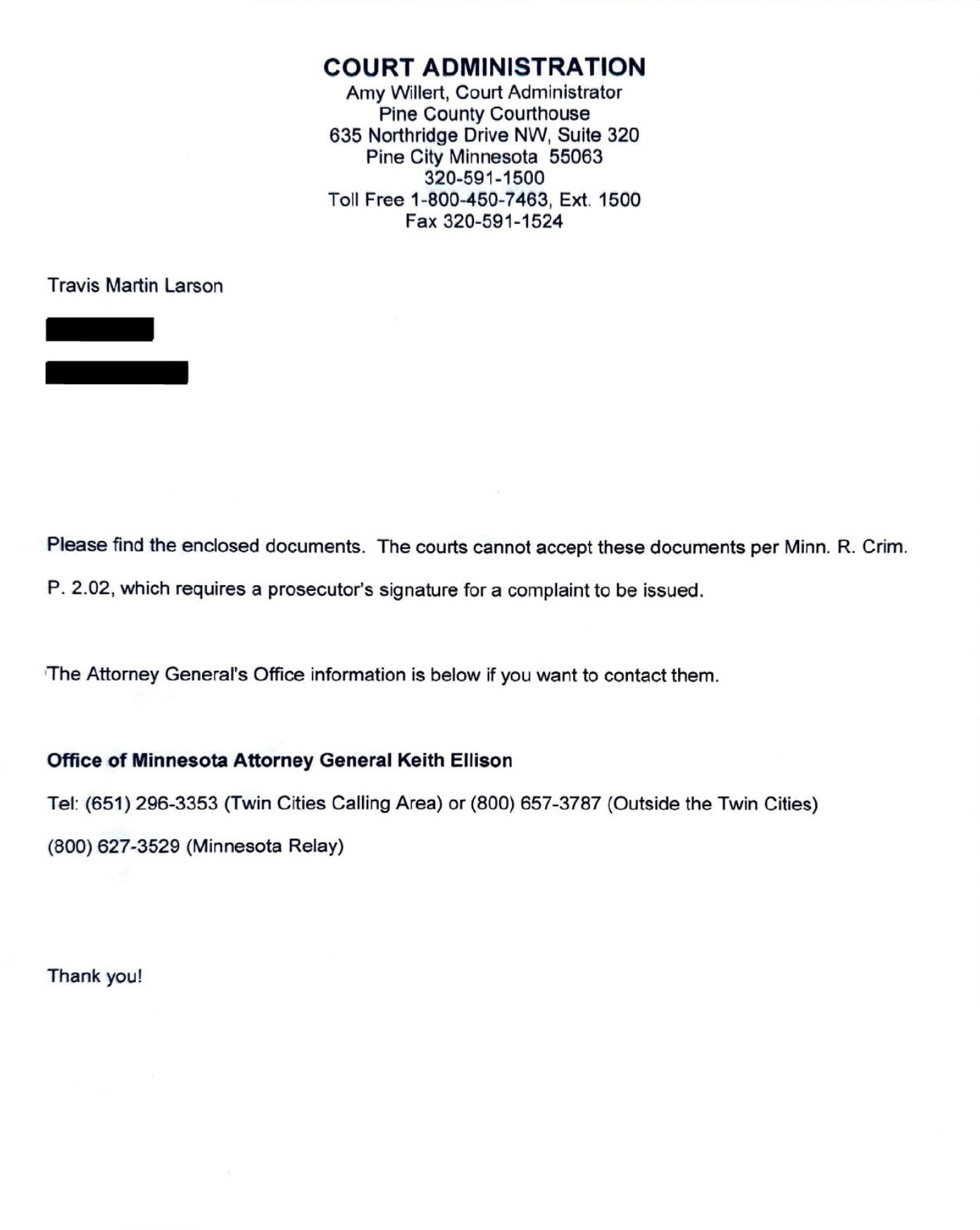

The court’s answer? A rejection slip. Minn. R. Crim. P. 2.01 gave me the right to swear a complaint under oath. But Rule 2.02 blocked the process — no complaint can issue without a prosecutor’s signature. In other words: citizens can sound the alarm, but only the gatekeepers get to pull it. And the gatekeepers were the very people I was charging.

I called the Attorney General’s Office. They told me flatly: “We don’t handle those complaints.” I recorded it. When Ellison refused to act, I sent the complaints to the Pine County Attorney’s Office. They admitted they “had them,” then went silent. No action, no response. I tried Governor Walz — asked to get on his cullender to ask him to direct Ellison to prosecute. His office gave me a boilerplate “we’re considering the meeting” and then no further contact.

Their silence wasn’t a dead end. It was an exhibit. Proof that oversight was dead, that the system had collapsed into self-protection. And proof that if I wanted accountability, I’d have to drag Pine County into court myself.”

The Criminal Complaints

“Rejected by the courts, stalled by the defendants”

The State of Minnesota

V

Reese Frederickson

The State of Minnesota

V

Jeff Nelson

The State of Minnesota

V

Carl Hawkinson

10th District Court

Response

Pine County Attorney

Response

“We’ve received your complaints”

The Civil Complaints

“Accepted by the courts, stalled by the defendants”

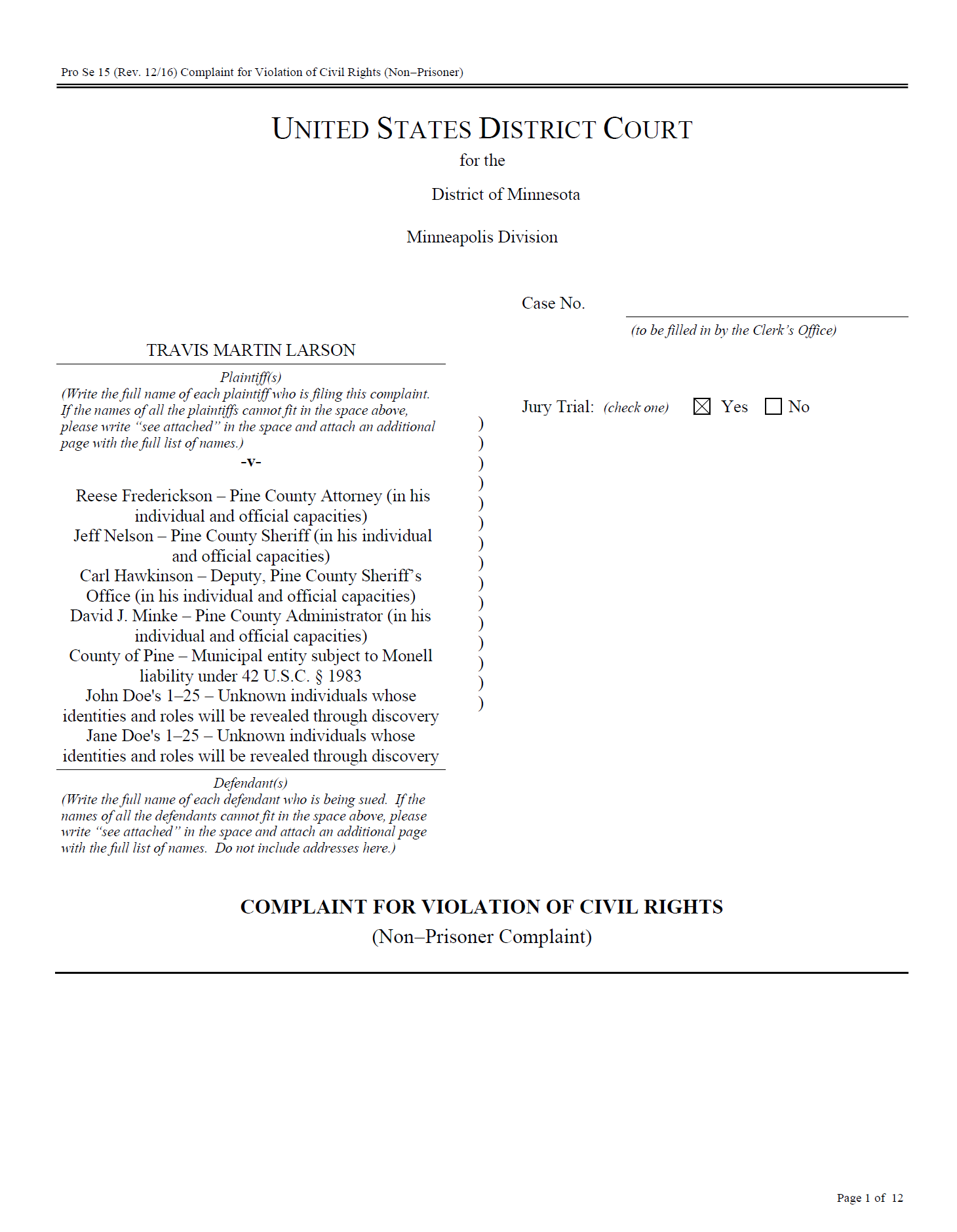

When the criminal route was blocked by the very people I charged, I forced accountability into federal court. On July 2, 2025 — days before Independence Day — I filed a civil rights complaint under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota.

I didn’t aim low. The defendants included Deputy Carl Hawkinson for the unlawful detention and retaliatory HRO, Sheriff Jeff Nelson for the cover-up and falsified reports, County Attorney Reese Frederickson for weaponizing his office and burying my filings, County Administrator David Minke for liability and oversight failure, and Pine County itself under Monell. I also included John and Jane Does 1-25 to cover those yet-identified. Their names weren’t just in rumors anymore — they were in a federal caption: Larson v. Frederickson, Nelson, Hawkinson, Minke, and Pine County,.

Filing wasn’t symbolic — it was strategic. § 1983 gave me the cause of action. § 1988 gave me the right to recover fees. Harlow v. Fitzgerald made clear that qualified immunity doesn’t shield officials when rights are clearly established. And they were: free speech, free press, due process, equal protection. Add the Seventh Amendment guarantee of a jury trial — proof that ordinary citizens, not insiders, would weigh their misconduct.

This complaint was a record bomb. I didn’t just tell a story — I attached evidence: exhibits, letters, rejections, proof of retaliation. Every statute cited, every exhibit attached, every page sworn into the docket. The silence and stonewalling of oversight became part of the evidence against them.

And the court accepted it. The clerk stamped it, the docket lit up, and summonses were issued. After years of being ignored, Pine County’s misconduct now lived on PACER, in black-and-white. They couldn’t shred it, bury it, or pretend it never existed. They were defendants.

July 2 wasn’t just a filing date. It was a line in the sand. Pine County wanted silence. I gave them a federal lawsuit.

This Timeline is the record Pine County never wanted exposed. It shows every abuse of power, every attempt at intimidation, every complaint stonewalled, and every oversight body that failed. It documents how a deputy weaponized his badge, how a sheriff buried the truth, how a county attorney used his office to retaliate, and how an administrator looked away. It proves, step by step, that accountability could never come from within.

The law is clear:

• 18 U.S.C. § 242 — criminalizes deprivation of rights under color of law.

• 42 U.S.C. § 1983 — creates a civil remedy when officials violate those rights.

• Monell v. Dept. of Social Services — holds counties liable for systemic abuse.

• Harlow v. Fitzgerald — strips away immunity when rights are clearly established.

• The First, Fourth, and Fourteenth Amendments — the rights Pine County trampled.

• The Seventh Amendment — the promise of a jury of citizens to weigh this record.

I did not choose this path. The facts and the failures left me no other. When oversight failed, I forced accountability into federal court. On July 2, 2025, the complaint was filed and accepted: Larson v. Frederickson, Nelson, Hawkinson, Minke, and Pine County, Case No. 25-cv-2753-NEB/LIB. That caption is not just mine — it is a marker of everything laid out on this Timeline.

From here, the story branches:

The [Legal Filings Archive] collects every complaint I’ve filed — state, federal, criminal, and oversight — each labeled with its outcome. These documents are not only proof of what happened, but also resources for anyone forced into the same fight.

The [Follow the Case] page tracks the federal lawsuit as it unfolds. Every motion, every response, every ruling will be logged there, one after another, so the public can watch Pine County defend the indefensible in real time.